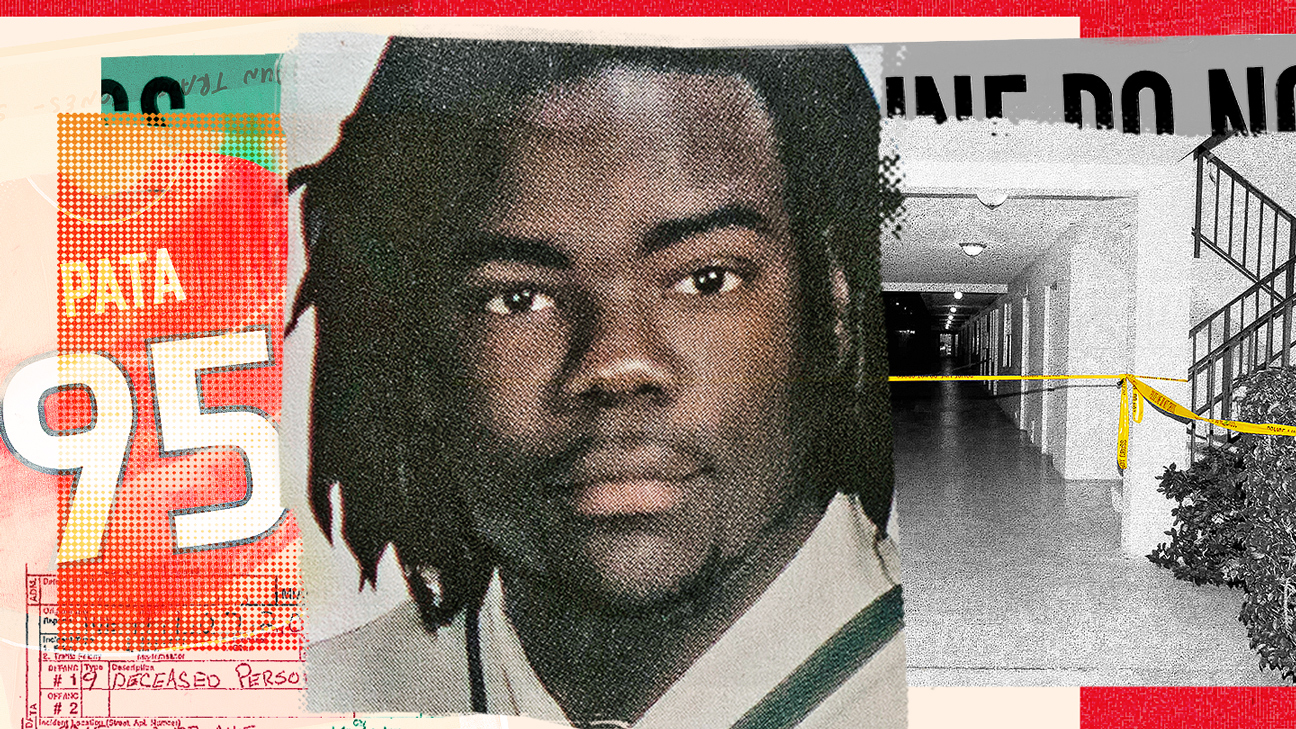

How a Deadly Police Force Ruled a City

After years of impunity, the police in Vallejo, California, took over the city’s politics and threatened its people.

via The New Yorker: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/11/23/how-a-deadly-police-force-ruled-a-city

Vallejo, a postindustrial city of a hundred and twenty-two thousand people, is best known for its Six Flags amusement park and for its musicians: E-40, Mac Dre, H.E.R. Its per-capita income is less than half that of San Francisco, and its population is more diverse, split among whites, African-Americans, Latinos, and Asians. Its police force, however, consists largely of white men who live elsewhere. Since 2010, members of the Vallejo Police Department have killed nineteen people—a higher rate than that of any of America’s hundred largest police forces except St. Louis’s. According to data collected by the anti-police-brutality group Campaign Zero, the V.P.D. uses more force per arrest than any other department in California does. Vallejo cops have shot at people running away, fired dozens of rounds at unarmed men, used guns in off-duty arguments, and beaten apparently mentally ill people. The city’s police records show that officers who shoot unarmed men aren’t punished—in fact, some of the force’s most lethal cops have been promoted.