Check out this video on YouTube:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e-WnHyV7sDg&feature=youtube_gdata_player

Film, longreads, books, TV, podcasts, gaming, live events.

Check out this video on YouTube:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e-WnHyV7sDg&feature=youtube_gdata_player

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J_vL3oJ4XMk

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hrsX1J1hVaM

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QLq3JpzYifM

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V7CBgxdsolo

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KBVgIX-Lqrw

All for a Few Perfect Waves: The Audacious Life and Legend of Rebel Surfer Miki Dora, by David Rensin

Why did I never know about Miki Dora before? How nice to meet a brother on the path, even if I’m not a surfer. Check it out:

Dora played the game as only a natural can. Soul surfing— surfing for the sheer art and pleasure of it— was his church long before the term was coined, and his passion for worship was equaled only by his drive to create and sustain a lifestyle that gave him the liberty to live free to seek thrills, spontaneous adventure, waves, and wonder, wherever he could find them.

Dora was there surfing Malibu at the beginning. The beginning is always a good place to be, except that you get a front row seat at seeing the mainstream come in and ruin things. Greg Noll remembers:

The whole Hollywood bullshit deal just brought more assholes over the hill from the Valley. If you’re from the Valley, don’t take offense, but this is basically what the beach guys thought. When you watch Stacy Peralta’s documentary, Riding Giants, they ask the guys, “What did you think of the Hollywood movies and surf music?” Answer: It was just a bunch of shit. Take the movie Ride the Wild Surf; it shows Tab Hunter and his friends sitting in the water, not a hair out of place, water calmer than a fish pond, no surf in the background. Suddenly someone yells, “Surf’s up,” and they cut to the same guys riding twenty-foot waves. Man, who’s gonna belive that? It’s one of the biggest laughs in the movie.

I guess I should say this before quoting more: Miki Dora lived to surf. He never sold out. A true soul. In fact, he would be against this very book about his life, which was only published after his death.

I go into contests once or twice a year for the pleasure of shaking up the status quo…the more restrictive they can make a contest’s (rules), the less (the judges) have to think or know about what you’re accomplishing in the water; thus making an easy job easier at our expense. What do these people care about your subtle split-second maneuvers, years of perfecting your talents?

I can relate to that, though I cannot claim the purity of Dora’s complete devotion to his art. I’m also leaving out a big part of the book that details Dora’s exploits funding his lifestyle without holding down a job and spurning most of the income his fame could have brought in. Lots of scams ensue and everyone compares his life to the film Catch Me If You Can. But here’s a paragraph to end everything with and send you on with the rest of your boring life. It’s Dora:

My whole life is this escape; my whole life is this wave I drop into, set the whole thing up, pull off a bottom turn, pull up into it, and shoot for my life, going for broke man. And behind me all this shit goes over my back: the screaming parents, teachers, the police [laughs], priests, politicians, kneeboarders, windsurfers, they’re all going over the falls into the reef; headfirst into the motherf*cking reef, and BWAH! And I’m shooting for my life. And when it starts to close out I pull out and go down the back, and catch another wave, and do the same goddamned thing again.

Five stars.

It’s been so long since I posted a book review. It’s not that I stopped reading books, it’s that I just didn’t finish any. After carefully cataloging my library, I realized that I had started over thirty books in the past several months without finishing a single one. Time to get focused. So here’s a review of a book I got (and finished) over the holidays.

Kill Bin Laden: A Delta Force Commander’s Account of the Hunt for the World’s Most Wanted Man

Writing under the pseudonym Dalton Fury, a commander of the elite Delta Force tells about the attack on Taliban and al Qaeda forces at Tora Bora in late 2001, when Usama bin Laden escaped capture. Here’s a little bit about how Delta operates, and when I read it I thought about the company I work for:

In Delta, as in the most successful Fortune 500 companies like GE, Microsoft, and Cisco, the organization makes the individual its number-one priority. It teaches, nurtures, and implements bottom-up planning. That is the direct opposite of the U.S. Army’s structured and doctrinally rigid military decision-making process, which is too slow and inflexible for fast-paced, high-risk commando missions or minds, and one undeniably driven from the top down.

This won’t be much of a book review, other than to say that Fury provides a detailed account of his operators and their frustrations with the mujahideen soldiers hired by the CIA to help in the battle. Another quote:

The fundamental Delta principle has long been “Surprise, Speed, and Violence of Action.” It aplies to commando tactics. If during an assault you lose one element, the implied response is to increase it in the next. For example, if we lost surprise during a stealthy approach to a target before reaching the breach point, we would increase the pace from a deliberate move to a stepped-up jog or sprint. At the breach, if it became obvious to the team leader that whatever or whoever waited on the opposite side of the door or window was alert and expecting visitors, we escalated to an even more violent explosive entry.

In writing this review, my mind is obviously more focused on strategy and tactics than recounting Fury’s tale. But his is a story worth reading.

Kill Bin Laden: A Delta Force Commander’s Account of the Hunt for the World’s Most Wanted Man

Stolen Innocence: My Story of Growing Up in a Polygamous Sect, Becoming a Teenage Bride, and Breaking Free of Warren Jeffs, by Elissa Wall with Lisa Pulitzer

The raid on the FLDS Church’s YFZ ranch in Texas has changed the landscape of the FLDS story. Now that FLDS members are speaking out about their own lives, we’re starting to see things get a little more balanced. At least for the moment, the anti-FLDS crowd has to share the microphone with the FLDS themselves.

But this book is Elissa Wall’s turn at the microphone. And since Elissa is the person whose experience as a child bride resulted in the imprisonment of the FLDS prophet, Warren Jeffs, you can count on polarized opinions. People seem to love her or hate her. FLDS members, some of whom will read this review, probably see Elissa (or at least her work to imprison Warren and sue the church and UEP) as a tool of Satan. People on the outside see Elissa as a child bride and rape victim.

However, no one would say that Elissa Wall had a happy teenage experience. Her memories of childhood in a home with three mothers are bleak, with inter-wife rivalries and jealousy. Let’s be honest: polygamy is almost always a hard life of sacrifice and challenge, even when it works. That’s why its believers call it a higher law. They would say that greater challenges lead to greater blessings. But for Elissa, there were few blessings.

The most intriguing character in the book is Elissa’s mother, Sharon Steed. Her story couldn’t be a bigger downer, and I repeatedly wished I was reading her biography written by one of the great authors (if only such a title existed). Her life, as accounted in this book, is filled with heartbreak and loss even as she remains faithful to her religion. Troubles in the home result in various shuffles in her plural marriage. One wife and her children are removed from the home, then brought back while another is shuffled out. The kids endure countless separations The Wall family struggles to stay together, believing that if they just keep trying heavenly blessings await.

As Elissa’s older siblings grow up, many become disillusioned with the faith and leave for the outside world, and contact with them usually ends at that point. These family breakups are very hard on Elissa as a child, but I sense they caused immense pain for Sharon.

The sad thing throughout is to watch Sharon, as portrayed here. She is apparently a true believer, but her life is constantly beset with woe. Eventually she and her children are reassigned to Fred Jessop, who she later marries.

Uncle Fred is the one who, according to court testimony, set up the fateful marriage between 14-year-old Elissa and her cousin Allen Steed.

Looking at the trial, I always wondered why Warren Jeffs was the only one charged with crimes related to pushing this marriage ahead and trying to keep it together. Allen, the alleged rapist himself, was only charged after Jeffs’ trial. Others pushing the marriage forward were Elissa’s own family, especially her mother. From Elissa’s account of the wedding day:

“Do you, Sister Elissa, take Brother Allen, by the right hand, and give yourself to him to be his lawful and wedded wife for time and all eternity?” Warren repeated in a voice that made the question sound like a command. Even as the silence grew unbearable, I still couldn’t bring myself to formulate the words. Suddenly, I felt my fingers being crushed by my Mom’s death grip. It shocked me into the moment, reminding me that I had no choice but to respond. “Okay,” I said, almost in a whisper. “I do.”

The marriage between Allen and Elissa was doomed to failure. Never mind that she remembers him teasing her as a child, calling her “Tubba Tubba.” But there were bigger issues. Elissa knew nothing whatsoever about sex.

It felt like we were having marital relations all the time, at least once or twice a week.

And I don’t think Allen knew much more. Even put in the best possible light, this relationship was ugly.

“This is going to be the exact same thing all over again,” I blurted out. “All your promises, they mean nothing. Nothing has changed.”

“I’m doing it out of love,” Allen declared. Everything he did was a contradiction, and before I knew it he was playing the guilt card again. As he continued to put his hands all over me, I just froze.

“Okay, fine,” I uttered. “Get it over with.”

I covered the Warren Jeffs trial, so much of the book was a repeat for me. But Elissa offers bits of commentary. Some of it doesn’t quite reconcile for an objective reader. If you are in one camp or another (FLDS or anti-FLDS), you probably already reject or accept her entire book. But for someone in the middle, trying to see all sides, I had questions. For example, Elissa attacks Jennie Pipkin for being a tool of the defense without realizing that she’s filling a similar role for the prosecution.

“If a wife rules over her husband, is that considered a bad thing?”

“No,” she (Pipkin) answered firmly. “I do what I want whether we agree or not.”

Her statement shocked me. She was outwardly defying so many teachings of the FLDS in a desperate attempt to prove a point for the defense.

That one was especially confusing, since it comes after many pages that describe Elissa breaking so many rules of the FLDS lifestyle against her husband’s wishes, and not getting into much trouble over any of it. She’s rocking out to Bon Jovi, watching television, sneaking around, partying, and spending nights sleeping in her truck. None of that behavior seems to get her in much trouble, though Pipken testifying in court that she can can do what she wants is labeled a shocking statement.

At another point in the trial, Elissa recounts mouthing the word, “hi” to a defense witness on the stand. Even if they had once been friends, this act seems a little bizarre to me considering that the intent of Elissa’s own testimony was to imprison the defense witness’s spiritual leader and prophet. Not to mention her lawsuits targeting the community.

Elissa sometimes comes across as naive. But to be clear, that naivety may not be her own fault. Elissa Wall is a product of her upbringing, and that raises serious questions about parenting, education, faith, and who we choose as our spiritual leaders. Her situation, which may or may not be common in the FLDS church, is a troubling mark on the reputation of Warren Jeffs and his followers. Here she recounts her last meeting with her mother, who remains a member of the FLDS church:

My sister stared over me at Mom. “I don’t feel like you have the power to stop something from happening to those girls. I don’t feel like you have the power to protect them.”

“Yes, I do,” Mom insisted. It was sad to hear her trying to convince herself of that. I knew how much she loved those girls, and that she would never want any harm to come to them. But the ominous sight of the white truck with the tinted windows was an ugly reminder of what lengths these people would go to keep a hold on their followers.

“No you don’t,” Kassandra (Becky Musser) shot back. “You didn’t have it when it happened to Lesie (Elissa), and you won’t have it when it happens to those girls.”

“Well, that’s just something I’ll just have to put on a shelf,” Mom said, referring to her inability to halt my marriage to Allen. It seemed that no difficult conversation with Mom had ever been complete without this line.

“I’d rather see you die than fight the priesthood,” Mom said. Her words were a hard slap on the face. Everything Mom had ever done had been influenced by her loyalty to the church above all else, but to hear her phrase it in such indisputable terms was upsetting.

Sharon, I’m dying to read your story. And those of so many others.

I’m a big fan of hearing all sides of a story. Having absorbed books and documentaries that take a pro-AIM (American Indian Movement) slant on the takeover and 71-day siege at Wounded Knee in 1973 I happily delved into the 600+ pages that make up FBI Special Agent In Charge Joseph Trimbach’s American Indian Mafia. Be forewarned, it’s a book filled with detail and argument.

Trimbach takes aim at media coverage that overlooked the fact that the village was taken over, looted, and burned by militant activists:

The reporters who covered Wounded Knee probably thought they were doing the right thing by granting credibility to people who advocated violence as a means to effect social change. But, by coloring a story the way Wounded Knee was, the media created a major problem for themselves: they soon became a distinctly unreliable source of information. The media missed covering the most important stories of the occupation: those of the people victimized by the takeover, and those rumored to have entered the village never to be heard from again. Granted, much of the hidden tumult probably occurred in April, after much of the press had lost interest. Still, it is fair to ask the question: did the media, in its rush to give AIM favorable coverage, overlook the violence perpetrated against ousted villagers and victimized infiltrators, some of which may have occurred right under their noses?

The book came at an interesting time. I was heavily involved covering the raid on the YFZ ranch, where more than 450 children were removed from their polygamous families amidst a horde of media and little bits of controlled information released by the government. Trimbach examines the legacy of Wounded Knee:

The deficit of knowledge may be partly due to not properly recording the event. At the time government archivists should have been paying attention to what was really happening in the village, Watergate and the ever-changing Directorship drew the focus away to political considerations. Because Headquarters was not engaged in the day-to-day conflict, and chose to stay that way, they were unaware of how precarious the situation was becoming. My recent attempts to revive interest in telling the true story of Wounded Knee have not met with great enthusiasm. Despite several attempts to convince Bureau personnel of the need to include Wounded Knee history in the official record, the FBI’s recently updated Minneapolis Office web site (as of this writing) still reflects inexplicable amnesia with not one mention of what was the most historically significant operation in Bureau history. What Headquarters officials (still) do not understand is that the topic should not be left to ideologues and extremists. What bothers me the most about this conspicuous failure is that the Bureau has ignored a history worth remembering, namely, that of hundreds of their own Special Agents and support personnel in rare service to their country.

Throughout Trimbach’s book, he points out where he feels the focus should be in the history of the event: squarely on the crimes committed. Like militants firing on Marshals and FBI Agents. Like the looting and burning of the trading post. Like the desecration of the village’s Catholic Church. And finally the brutal execution of two FBI agents. Trimbach argues that no amount of government corruption or police brutality should justify murder.

Bob Taubert recalls the grisly scene, hours later: “The Agents had been dead for some time. Rigor mortis had set in, and both bodies were covered with flies in the hot sun. When I saw the makeshift bandage, I immediately surmised that Ron had tried to save his partner. The totality of it hit me hard. I was sitting on the hill with my head in my hands, unable to comprehend why someone would do this. By now, the press had started to swarm. A female reporter came rushing up to me and said, ‘What happened, what happened here?’ I looked up at her and motioned toward the bodies. ‘I don’t know, lady. Why don’t you ask them?’”

More on the murders, as he dissects Matthiessen’s “In the Spirit of Crazy Horse”:

When Agents Jack Coler and Ron Williams drove onto Pine Ridge, they were acting under the knowledge of an existing arrest warrant for Jimmy Eagle. Furthermore, there is no prohibition against FBI Agents’ presence on federal reservations. In fact, their sworn duty is to investigate serious crimes in Indian Country.

To make this tale sound even more sinister, Matthiessen takes it a step further. With a conspiratorial ear turned to his AIM friends, we learn the dark secret that the Agents drove onto the reservation that fateful day in June of 1975— with their long guns safely locked in the trunks of their cars— acting as an advance team for an all-out assault on the practically defenseless AIM members who were minding their own business. And that, “…paramilitary forced had been surrounding the Oglala region all that morning…” and “…within a remarkably short time, reinforcements arrived that can only be called massive, when set against of band of untrained men and boys armed mostly with .30-30 deer rifles and .22s.”

What’s not explained in this fantastic story is why a large force of BIA police, FBI Agents, and law enforcement officers, supposedly standing by with massive firepower, arrived too late to save the Agents from being murdered. Or, for that matter, how “deer rifles and .22s” were able to hold off “massive reinforcements” at all. In another twist, depending on which one you prefer, the Agents unknowingly served as sacrificial lambs, used as bait to draw out the peace-loving Indians for one big shootout, a massacre the white law enforcement men had been wanting for a long time. (Matthiessen’s looniest ideas are often the most vicious.)

Trimbach pulls from recent events in the hunt for the killers of Anna Mae Pictou Aquash, including this chilling testimony from the 2004 trial of Arlo Looking Cloud:

McMahon: Tell the Court as best you remember exactly what he (Leonard Peltier) said.

Ka-Mook: Exactly what he said?

McMahon: Exactly what he said.

Ka-Mook (extremely upset): He said the motherf*cker was begging for his life, but I shot him anyway.

According to Trimbach, the historic version of the takeover of Wounded Knee by the American Indian Movement (AIM), has been dominated by pro-AIM voices. Reading his book has reminded me how important it is to listen to all sides of the story when forming an opinion.

Breaking News: A Stunning and Memorable Account of Reporting from Some of the Most Dangerous Places in the World, by Martin Fletcher. [rating: 4/5]

Martin Fletcher, the NBC News Bureau Chief in Tel Aviv with a penchant for posing on top of destroyed tanks, provides a great look back at his life covering conflict.

War reporters face moral dilemmas all day: Is it reasonable to film a crying woman two feet from the lens? How about a lost child screaming for its parent? Should one film him or take him by the hand? If a man is to be executed and the soundman’s gear suddenly doesn’t work, what do you do? Delay the execution? That’s what the BBC’s David Tyndall did in Biafra in 1970, when he yelled, “Hold it, we haven’t got sound,” and the quivering man about to be killed had to suffer that much longer while the soundman sorted out his gear. Later, Tyndall was mortified by his instinctive response to the dilemma, as was the BBC, which severely reprimanded him. But every move in this job poses a different dilemma, and nobody can be right all the time. In fact, the most critical question is usually not moral in nature but practical: How far down this road can I drive and stay safe?

Fletcher takes us through his experiences beginning with the Yom Kippur War in Israel and then on throughout Africa (Somalia, Rwanda, Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), South Africa), Cyprus, Afghanistan, etc. This from Albania, covering the Kosovo war:

Then there was the small matter of the bandits who preyed on travelers, especially foreign journalists flush with cash. One BBC television team hired a small truck and driver. Just as they were approaching the final leg of the journey into the country’s wild and poor northeast, they ran into a group of armed men who stopped their vehicle at gunpoint and demanded money. The producer handed over his shoulder bag with envelopes of cash, and they were allowed to proceed unharmed. The team was shocked, but the producer chuckled and said, “Don’t worry, I’m not dumb, that was just a token in case we got robbed. The real money is in my boot.” The team laughed with relief, whereupon their Albanian driver stopped the car, put a gun to the producer’s head, and stole the rest of the money. Then the driver forced everybody out and drove off with their gear. And he was one of the good guys.

Breaking News: A Stunning and Memorable Account of Reporting from Some of the Most Dangerous Places in the World, by Martin Fletcher. [rating: 4/5]

Roberts Ridge: A Story of Courage and Sacrifice on Takur Ghar Mountain, Afghanistan.

[rating:5/5]

I’ve been spending a lot of time this week with the Navy SEALs in Afghanistan. This book by Malcom MacPherson, is another look at the events on Takur Ghar, where several special ops warfighters lost their lives to Taliban and/or al Qaeda fighters. I found it an interesting counterpoint to Naylor’s amazing book, Not a Good Day to Die: The Untold Story of Operation Anaconda. Where Naylor quoted other operators critical of the SEALs that day, MacPherson’s book is told from the SEALs point of view. He doesn’t cover up their mistakes, but he doesn’t pile on.

Fifty feet above the ground, as soon as Calvert flared the Chinook, bullets crashed through the chin bubble. in the right seat, he watched as holes pinged through the windshield glass. Two bullets hit his helmet and jerked his head left, as if a hammer had slammed his skull. In the same spray of fire, he was shot eight times across his chest, one bullet lodging in the Kevlar armor while seven flecked off.

It’s a great tale of a tragic battle on the very top of a 10,240 foot mountain peak. One more intersting quote:

A former SEAL had joined SOAR for thrills, and if that didn’t say enough already, in one of his first training sessions he was taking off a Chinook and was powering through 150 feet when his instructor in the next seat leaned over and shut down both engines. The SEAL’s eyes widened and he screamed, “What the f*ck are you doing?” The instructor folded his hands as the bird autorotated in its powerless descent, hard to earth.

Roberts Ridge: A Story of Courage and Sacrifice on Takur Ghar Mountain, Afghanistan.

[rating:5/5]

[rating:4/5]

For a while, it’s fun watching legendary cinematographer Haskell Wexler berate his son Mark, who has turned the camera on his father. After the thrill of that gets old, you’re pulled into the father-son dynamic.

Starring: Peter Bart, Verna Bloom Director: Mark Wexler

Plot Synopsis: Mark Wexler’s cinematic blend of biography and autobiography centers on his relationship with his father, legendary Oscar-winning cinematographer and filmmaker Haskell Wexler, whose long and illustrious career is a virtual catalogue of 20th-century classics. Haskell’s collaborations with such world-class filmmakers as Elia Kazan, Milos Forman, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola and Mike Nichols include such works as WHO’S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF?, AMERICAN GRAFFITI, COMING HOME, BOUND FOR GLORY and ONE FLEW OVER THE CUCKOO’S NEST. The film features interviews with many of these artists, along with such luminaries as Jane Fonda, Michael Douglas and Sidney Poitier. But the true “star” of TELL THEM WHO YOU ARE is Haskell himself, a controversial, larger-than-life character who challenges his son’s filmmaking skills while announcing with complete conviction that he could have done a better job directing most of the movies he’s shot. As these two men swap positions on camera and behind it – sometimes shooting one another simultaneously – the film looks with honesty and compassion at their attempts to reconcile before it’s too late.

While Europe Slept: How Radical Islam is Destroying the West from Within, by Bruce Bawer.

[rating:5/5]

Bawer describes fast-growing Muslim communities throughout Europe that are basically isolated and closed off from European society. Muslims in France, Denmark, the Netherlands, haven’t been integrated into the countries they’ve emigrated into. They live in ghettos that are often beyond the control of local authorities. And they bring with them cultural norms from their old countries, like the lack of rights for women and honor killings, which violate the law of their adopted West European countries:

In London in 2003, a lively sixteen-year-old London girl named Heshu Yones- who’d fallen in love with a Lebanese Christian boy and planned to run away with him- was stabbed eleven times by her father, who then slit her throat. In a farewell note to her father, Heshu referred to the frequent beatings he’d given her:

Bye Dad, sorry I was so much trouble.

Me and you will probably never understand each other, but I’m sorry I wasn’t what you wanted, but there’s some things you can’t change.

Hey, for an older man you have a good strong punch and kick.

I hope you enjoyed testing your strength on me, it was fun being on the receiving end.

Well done.

The book definitely walks a fine line of being labeled a paranoid right-wing screed against foreigners invading these long-white countries. In many similar situations, people pointing out these kinds of situations and statistics have been labeled racist. The fact that Bawer is a gay man sometimes makes it seem okay, and sometimes you’re left wondering if you should be agreeing with his points.

Bawer details of the use of the host country’s welfare system by those looking to bring down the very western society that is supporting them:

After the 2005 terrorist attacks on London, it emerged that the four suspects had raked in more than half a million pounds in welfare benefits from the British government. The Telegraph reported, too, that Hizb ut-Tahrir founder Omar Bakri Muhammed (who preached that “we will conquer the White House… we will be in charge and Muslims will control the earth”) was getting “£331.28 a month in incapacity benefit and £183.30 a month in disability living allowance”; in addition, he collected a “housing benefit” and a “council tax benefit,” not to mention his wife’s welfare intake of “at least £1,300 a month.” (Curiously, no mention was made of child benefits for his seven progeny.) Even his car had been acquired free of charge under a government program.

Bawer talks of the European way of dealing with its growing Muslim population- appeasement:

“Muslims have a dream of living in an Islamic society,” declared a Danish Muslim leader in 2000. “This dream will surely be fulfilled in Denmark… We will eventually be a majority.” A T-shirt popular among young Muslims in Stockholm reads: “2030- when we take over.” In many places in Europe, agitation for the transfer of sovereignty has already begun. In France, a public official met with an imam at the edge of Roubaix’s Muslim district out of respect for his declaration of the neighborhood as Islamic territory to which she had no right of access. In Britain, imams have pressed the government to officially designate certain areas of Bradford as being under Muslim, not British law. In Denmark, Muslim leaders have sought the same kind of control over parts of Copenhagen. And in Belgium, Muslims living in the Brussels neighborhood of Sint-Jans-Molenbeek already view it not as part of Belgium but as an area under Islamic jurisdiction in which Belgians are not welcome.

And as the United States wages a war on terrorism, European distrust of US intentions leads them to often, in Bawer’s words, side with the terrorists:

Jordan wanted Mullah Krekar on drug-smuggling charges ( a year later, he and fourteen others were charged by Jordan with planning terrorist acts against United States and Israeli targets), and U.S. officials wanted to talk to him too. But the Dutch, frowning alike on Jordan’s indelicate treatment of suspected terrorists and on America’s death penalty, would not extradite him. Instead, they held him until January, then put him on a plane to Norway on the understanding that he would be arrested at the airport in Oslo. But Norwegian authorities- who shared their Dutch colleagues’ unwillingness to hand him over to either Jordan or the United States- allowed Krekar to walk free.

Coming in for some serious criticism from Bawer is France, who he repeatedly mentions had business dealings with Saddam Hussein’s government before the US removed him from power:

One might have thought this kidnapping would help Frenchmen see that all Western democracies were in this together; instead, the French government strove to get the message through to the hostage takers that in the war between Islamism and America, France was on the Islamists’ side. Le Monde applauded this spineless tactic. While pointing out thtat no democracy- not even France- was safe in the holy war that had begun on 9/11, the newspaper’s editors went on to celebrate (in typically frlowery French-editorial prose) the fact that the hostage taking, instead of exacerbating tensions between French Muslims and non-Muslims, had instead “caused of movement of national communion, almost of sacramental union.” Why? Because French Muslim leaders (who, practically speaking, could hardly have done otherwise) had unanimously denounced the nabbing of Malbrunot and Chesnot, expressed their loyalty to France, and sent envoys to Baghdad to help free the journalists. That’s it: all it takes for the French intelligentsia to wax poetic about “sacramental union” and about “the Muslims of France” being “the first in line to defend the Republic” is for French Islamic leaders to be willing to dissociate themselves from a patently barbaric act.

Looking to the future:

Over dinner, in response to Hedegaard’s dark view of Denmark’s future, Brix was more hopeful. The media would eventually come around; crisis would be averted. “You ahve to be a little patient,” she said. Not until the Eiffel Tower and the Tivoli in Copenhagen were blown up, she said, would the elite get it. hedegaard agreed. But then again, he said, the destruction of those landmarksmight have exactly the opposite result- the media might simply intensify its perverse cries of “Why do they hate us so much? What have we done to deserve this hatred?” the Wester European attitude, he observed, is that “of a repentant criminal”: too many Europeans are simply too willing to compromise their freedom. He mentioned a Danish firm with which he was familiar. It had recently taken on some new Muslim employees, and one of the longtime workers there had asked, in all seriousness: “When the Muslims start working here, can we still wear shorts in the summer?” Such readiness to adjust to Islamic norms- an attribute rooted in the fact that the reigning social ideal was not liberty but compromise- did not bode well for Denmark’s future.

One more, somewhat unrelated quote:

Jose’s language skills were in his blood. His father had been a journalist under Batista. When Castro and Guevara came to power, they arrested Jose’s father, tortured him, and put his eyes out. On the day I met him, in his modest ground-floor apartment, he sat in an upholstered chair in a book-lined room and spoke to me with a courtliness and respect to which I was not accustomed. Ever since then, every time I’ve seen a Che T-shirt on some clueless young person, I’ve thought of Jose’s father sitting in his living room, surrounded by books he could no longer read.

While Europe Slept: How Radical Islam is Destroying the West from Within, by Bruce Bawer.

[rating:5/5]

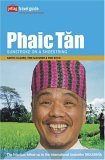

The Jetlag travel guide to Phaic Tan: Sunstroke on a Shoestring.

This is the second Jetlag travel guide, coming on the heels of last year’s spot-on paradoy of an Eastern Europe guidebook: Molvania (link below).

If you’ve ever read a travel guide in anticipation for a trip, you’ll appreciate the humor and the level of detail in the Jetlag books. Why hadn’t someone thought of this before? Check it:

Many western visitors to Phaic Tan are terrified of the possibility that they may— even accidentally —end up eating dog. A good test when served any roast meat is to look closely at the animal’s head. While pigs and goats will traditionally have an apple stuffed in their mouth, dogs tend to be cooked holding a tennis ball.

Phaic Tan is all about a fictional country that is quite obviously a mix of Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Among the sights along Thong On’s “Mildew Coast”, one can “settle back in a lazy deck chair under a shady coconut palm and, on any given day, take in the sight of an overloaded passenger ferry slowly sinking in the glittering azure sea.”

Can’t really say enough about these books, and I can’t wait for the upcoming titles in the series. I mean, they actually came up with the phrase “after his former career as a Khmer Rouge Information Officer.” Check this:

If you think Phaic Tan’s heat and humidity are hard to take now, spare a thought for those who lived back before the arrival of electric cooling. In those days rooms were kept ventilated with a ceiling fan pulled by a young servant boy (mataak) who customarily sat outside. With the coming of electricity in the 1920s this system was modified; the young servant boy still sat outside pulling the fan but he had a wire cable attached to one toe and was given a jolt if he slowed down.

Phaic Tan, by Santo Cilauro, Tom Gleisner, and Rob Sitch, A.

And don’t forget:

102 Minutes: The Untold Story of the Fight to Survive Inside the Twin Towers, by Jim Dwyer and Kevin Flynn.

This book is a meticulous account of what happened inside the World Trade Center from the time the first plane struck until the second tower collapsed, 102 minutes later. From the authors’ note:

Like the passengers on the unsinkable Titanic, many of the individuals inside the World Trade Center simply did not have the means to escape towers that were promised not to sink, even if struck by airplanes. In the struggle to live, those who survived and those who did not sent out hundreds of messages. They gave us the history of those 102 minutes.

The level of detail holds your attention, and even though you know how the story ends, the writing invests you in the final fate of a variety of characters: firemen, businesspeople, and even the lowly security guard who stays at his post on an upper floor helping people evacuate. This book brings the horror home:

They peered out. Debris had rained onto the plaza— steel and concrete and fragments of offices and glass. Above them, they could see the east side of the north tower, and also its northern face. Instead of the waffle gridding of the building’s face, they now saw a wall of fire spread across ten or fifteen floors. Then they saw the people coming out the windows, driven toward air, and into air. The plane had struck not two minutes earlier.

The authors of this book are reporters for the New York Times who had previously covered the 1993 bombing attempt. As they recount the final moments of the Twin Towers, they also shine light on the various ways the towers were built on the cheap, with safety features being removed in the name of more rentable space. Also interesting is the NYFD response, and how inter-agency fueds may have contributed to the high death toll among firefighters.

This book puts you into the buildings, and with each turning page you are frantic, knowing the end is closing in:

The word to leave finally got to Steve Modica, the aide to fire chief Paolillo, who had watched, uncomprehending, as police officers pounded down the stairs at the 30th floor. A fire captain, coming down after the police officers shouted at him.

“Evacuate! Evacuate! I want everyone to evacuate the building.” Then the captain continued down. Modica tried to reach Chief Paolillo, but couldn’t raise him. He switched to all three channels used by the department. He still could not get anything. He considered the circumstances, and would recall thinking: “We were doing nothing. Nothing. What’s the plan? Nobody had a plan.” He started down the stairs.

102 Minutes, A.

Reading this book, I kept seeing a comparison to the early days of computing and the early days of punk rock. Andy Hertzfeld’s account of the design and engineering of the Macintosh computer certainly takes you back to early 1980’s California.

I remember going to computer shows back then with my dad, who seemed to buy any new product that showed any promise. I mean, we had a laser printer in the house when most people still had typewriters. To switch fonts, you had to shove in a new font cartridge (and those were like, $100 each). And I’ll never forget how we put our name on the waiting list for the Atari 2600 version of Pac-Man. The day we picked it up, my parents also bought the family an Apple II computer. I woke up at 5am to play with it before school, where all the other kids thought I was a liar for claiming to have Pac-Man and the computer.

Back to the book, you have to admire Apple’s then anti-corporate approach- like when the engineers rigged up a pirate flag over their building. Okay, that seems pretty tame, doesn’t it.

Bottom line, if you’re into computers and software design, this book will be interesting. Fans: B. Others: C.

An Exploration of the Last African Wilderness, by Peter Stark, Grade: A

Peter Stark’s account of a trip kayaking down Mozambique’s Lugenda River is an amazing tale. The previously uncharted 750-kilometer route is filled with rapids, waterfalls, crocodiles, hippos. And throughout the river adventure, he recounts the tales of historic explorers and wanderers throughout history. “Why are humans compelled to explore?” he wonders.

As I was raised on the European version of world events, it’s always fun to find yourself seeing the other side of the story. Hearing about Stanley and other explorers as a child, watching cartoons, Tarzan movies, and reading Edgar Rice Burroughs, I always thought that the Africans and their menagerie of beasts were the most dangerous things to encounter in Africa. Now that I’m older and have learned more, the most deadly thing to meet up with in Africa was probably the European unless you had a load of gold, rubber, or diamonds to give to them.

Stark recounts from da Gama’s visit:

The local king offered da Gama a ransom of gold plus the delivery of the Muslims whom he alleged were responsible for the grievously mistaken attack on the Portuguese trading post. Da Gama would have none of it. Instead, he captured eight or ten trading vessels coming into Calicut that did not realize the Portuguese fleet was anchored there; ordered his men to chop off the hands, ears, and noses of their crews; and sent the body parts in a boat to the King of Calicut, telling him to make a curry of the cargo. Da Gama had the still-living handless, noseless, and earless victims bound by their feet and their teeth knocked down their throats so they couldn’t untie the knots with their mouths; he had them piled in another boat, set it afire, and sent it ashore, too. When three members of one late-arriving Muslim crew pleaded that they wished to convert to Christianity before they were killed, da Gama showed them the mercy of having them baptized and strangled before they were hauled aloft and shot full of arrows like their fellow crewmen. Finally, the King of Calicut sent a large fleet against the Portuguese. Da Gama’s artillery blew that to splinters, too.

“No wonder the people we had just passed fled into the trees.

There is also in this book a great pair of river guides who embody every white South African macho archetype. These two are the only ones with the knowledge, skill, and physical ability to make the trip a success, and the author’s attempts to reconcile his own personality to theirs is well written with honesty and candor. His attempts to spend more time with actual Africans that they pass on the river is usually met with derision by the others in the group, who see little to learn from the locals and their often primitive ways.

Stark:

“We don’t have a word in our language for ‘wilderness,’” a native Mozambican villager would later tell me. “What you might call ‘wilderness’ we call ‘the place where no one lives and you are free to gather things.’”

What more can I say? Great book, A.

Though it won’t be published for another eight months, you’ve got to check out the preview to photographer Andrew Faulkner’s book, Midnight Train to Warsaw.

Night, Elie Wiesel, Grade: A

“If in my lifetime I was to write only one book, this would be the one.”

This new translation of Wiesel’s Night is a masterpiece in 120 pages. I know my holocaust books, and this is one of the most chilling I’ve read. This story of the young Elie being taken from a Hungarian ghetto to Auschwitz and Buchenwald is full of despair and horror. And as events unfold, unspeakable events, Wiesel recounts the death of his faith in the God he was raised to believe in.

I’ve been to Buchenwald and Auschwitz. There is a feeling there that cannot be described in words. The rare book like Night imparts a little of it, just enough to break your heart.

Remind me to send this book to the guy who made sure to tell me that Jews owned Werther’s Toffee company. He needs to read it and suck on some hard candy.